1. Nowadays Electricity Industry: State, Challenges and Trends

The history of utilising energy—from the very beginning of the rise of the human species who attempted to control the fire to nowadays cutting-edge technologies exploring the possibility of deploying energy from nuclear fusion—is also the history of the civilization of human beings [1]. Throughout the past and present, every energy revolution always leads to profound social change, liberating us from heavy labours to focus on other more significant activities: Around 10,000 years ago, human beings learnt to use fire to process raw food into mature and thus their body can allocate more energy to the brain rather than the digestive system; In the medieval era, a variety of man- and animal-powered tread-wheels as well as water- and wind-driven converters are developed leading to the prosperity of many civilizations [1]; In the modern world, electricity and fossil fuels have dominated our society in terms of industrial and food production, transportation and daily life, to name but a few. The energy sector, therefore, is such a fundamental but important field that has attracted amounts of attention from all parts of society.

According to the report published by the International Energy Agency (IEA) [2], the figure of global electricity consumption peaked at 24,739TWh in 2018. In 2020, the energy demand decrease was seen due to the COVID-19 pandemic, however, an outbreaking growth of 4.5% is expected in 2021, contributed by rebounding economic activities and the development of major economies [3]. As a consequence, the ensuing challenges are quite straightforward and has been discussed by people for many decades, e.g., global warming and imbalanced energy distribution.

On the one hand, the accumulation of energy-related CO2 emissions leads to global warming, threatening billions of inhabitants living in coastal areas. According to the report, the global CO2 emission keeps growing at a rate of 1.7% in the past three decades, even faster than the increase of energy demand in this period [3]. Because the increase of non-hydro renewable energy fails to compensate for the decrease in nuclear and hydro energy, the slow but continuous growth of using fossil fuels still remains, which is a main contributor to the increment. Announced as a pledge, energy-related net-zero emissions are set as an ultimate goal in 2050 by an increasing number of countries. Briefly, efforts focus on optimising energy efficiency, encouraging citizens’ participation, promoting electrification, applying renewable energy, to name but a few. However, so far, the promises of governments (even if they have been fully realized) are far from meeting the requirements [2]. On the other hand, the distribution of energy is imbalanced. Although power overcapacity has become a newly emerging problem for some countries, energy shortage is still unsolved and even more serious in some undeveloped regions. Experts clarify the imbalanced problem is because of the unbalanced development of electricity system [2], inefficient transmission process [4], out-of-date and unwise edge grid management [5], people’s unaware waste [6], etc. Except for government actions to intervene in energy pricing and upgrade infrastructures, accurate prediction and supply-demand matching can not only help to reduce the waste of excessively generated energy but also mitigate the shortage in remote regions.

Particularly, as the most important and fastest-growing end-use fuel, electricity is regarded as the most effective way to provide fundamental services, taking account for 20% of the global final energy consumption and more than 50% of the total CO2 emission in 2020 [3]. The dramatically increasing demands for electricity make it a scarce resource that should be carefully planned and managed. Therefore, related discussion continues for decades among both academia and the industry, concentrating on the three pillars in modern electricity systems, that is, electricity generation, distribution and consumption. For each of the three pillars, the advancement of modern technologies can make critical contributions. With the cost reduction for Variable Renewable Energy (VRE), the implementation of distributed energy resources, the advancing process of digitalisation and electrification, significant electricity system transformation is about to come [2]. However, the electricity system is such a complex and unforeseeable artefact also difficult to be well understood and managed by ourselves.

From the electricity consumption perspective, it is difficult to accurately predict short-term demand. For example, the electricity demand can soar dramatically when extreme weather suddenly comes. On February 16th, 2021, Texas state suffered from an unprecedented temperature drop. Because over 60% of residents in Texas use electricity for heating and the snow caused obstacles in electricity supply and transmission, the demand-supply balance was broken. As a result, the electricity price exponentially increased from 0.05$/kWh to 9$/kWh within one day [7]. Meanwhile, unwise waste of electricity is also very common in the existing facilities, which leads to low energy utilisation efficiency. For instance, studies show that Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems in buildings consume more than half of building electricity [8], but most of the existing HVAC systems are still manually controlled rather than automatically managed with respect to energy efficiency, leading to significant waste.

On the electricity generation side, although an appropriate combination among the various types of electricity generators, e.g., solar panel, wind turbine, tidal power collector, can complement each other, it is critical and difficult to make a trade-off between factors such as different installed capacity, generation seasonality, environmental impacts and economic cost. Furthermore, once the generators are installed and run, their generating capability is fixed in the short-term. In this way, flexible adjustment is almost impossible to match the rapid and unexpectable changes happened that on the consumption side.

Considering the above challenges, the distribution system is another important complement to the imperfect power system, typically consisting of electricity transmission and storage units. Energy loss on the transmission system is the main reason for lowering the energy efficiency, while the smart grid management technology and distributed energy resources realization is expected to aid. An excellent storage unit is expected to shave the peak and fill the valley by collecting the surplus generated electricity and supplementing power to the system as needed. Noticeably, the trade-off between maintaining the storage units and bearing the loss due to the waste/lack of electricity is crucial and difficult to be finely figured out.

Fortunately, a variety of powerful machine learning techniques have been applied to make critical decisions, analyse high-dimensional signals and control complex systems, so people also hope that AI technology can help us better optimize our power system and promote the power system transformation, whether it is from the perspective of electricity generation, distribution and consumption. This blog mainly aims to discover the potentials and ethical implications of applying machine learning techniques to electricity systems and introduces some pioneers who successfully integrate machine learning techniques to improve the electricity system effectiveness and efficiency.

2. How Machine Learning Techniques Will Change the Electricity Systems

As a data-driven method, a growing number of Machine Learning (ML) systems have presented significant potentials in the electricity systems. Thanks to continuous in-depth exploration, the predictive ability of machine learning models has been significantly improved. In fact, they can be widely used to optimise the electrical energy management on the consumption side, automatically adjust the electricity system for demand-supply matching on the generation side and find out the most economic- and energy-efficient storage and transmission solutions on the distribution side, etc. Different from traditional methods, machine learning-based approaches are expected to satisfy the needs of the ability to perform real-time predictions with accuracy, robustness as well as flexibility [9]. Therefore, what can be confirmed is introducing AI techniques into the electricity systems will significantly promote the incoming transformation and open a new era for future electrical energy generation, consumption and distribution.

2.1 Pillar I: Consumption

In this section, we mainly discuss two machine learning applications from the electricity consumption perspective, i.e., the electricity demand prediction and the energy efficiency optimisation for end-facilities, which are two vital challenges on the consumption side. We will see what advancement in this field that machine learning techniques bring to us.

Electricity Demand Prediction

Internally, electricity demand prediction is able to provide on-time and crucial information for electricity system managers to make significant decisions regarding electricity production and proper utilisation of the limited energy resources [10]. Meanwhile, the externality of precisely predicting the electricity is also obvious. Suganthi et al. in [11] and Torabi et al. in [12] clarified strong correlations between the energy demand and many social and economic concerns such as a country’s gross national income, advancement of technology and civil welfare, because electricity, as a fundamental production factor, has a profound influence on product price and decision process. Surprisingly, millions of dollars can be saved for just a 1% improvement in terms of demand prediction accuracy.

In 2017, Nikolaos et al. experimentally proved deep learning methods can represent the state-of-the-art approach to predict the day-ahead aggregated energy consumption, comparing to not only the traditional methods like older econometric regression and Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) but also traditional machine learning models such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF) [13]. In their study, a series of fully connected Artificial Neural Networks (ANN, also called Multi-Layer Perceptron, or its short form MLP) are explored. Before we move on to demonstrate their findings and contributions, it is worthy to briefly introduce how a typical MLP works. Inspired by the biological brain’s structure and the way it transmits information, the ANN is proposed [14]. Fig. 3 a) shows a simple MLP with an input layer, two hidden layers and an output layer, along with intuitive graphical demonstrations of forward and backward propagations in b) and c). Neurons and connections between them imitate the brain structure, while the non-linear activation in the neuron is applied to mimic the information transmission process between neurons. This structure has been proved as a successful example of bionics, which can deal with non-linear problems much better than traditional statistical learning models. To make predictions by comprehensively aggregating all the input features, forward propagation is conducted. For each neuron, it determines the output value by activating the aggregated and weighted information from the neurons in the last layer. To find out the optimal connection (or weights) scheme, the backpropagation is applied to approximate the global optimum by a variety of optimisation techniques such as Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD).

Back to the research by Nikolaos et al., they compared 25 sets of hyperparameters including the number of hidden layers, the number of neurons in each layer, dropout percentage, batch size, etc., and found that a shallow but wide network structure (one hidden layer with 32000 neurons) achieved the best result to predict the day-ahead electricity demand. Comparing to other traditional machine learning models, its Normalised Root of Mean Square Error (NRMSE) is approximately half of the best model—SVM with the linear kernel. However, it is still a challenge to set appropriate hyperparameters given a generalised scenario, because the simulations are based on a given dataset which may not represent comprehensiveness. Furthermore, there is a range of ANN variants such as the Long-Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model which suits the time series analysis problem better worthy for further exploration.

Energy Efficiency Optimisation for End-facilities

A considerable proportion of energy waste is caused by inefficient end-facilities, for example, old buildings with poor HVAC systems suffering from insufficient heat retention can lead to unnecessary electricity waste. Although the developing technology has helped us improve energy efficiency for many instances (e.g., compared to the incandescent bulb whose 90% of used energy is in heat, LED has saved a lot), uncountable energy is still being wasted and it is difficult to track. In fact, to achieve international climate and energy goals, energy efficiency takes the responsibility of 40% of energy-related greenhouse gas emissions reduction in the coming two decades [15]. In the short future, machine learning techniques are expected to provide certain potentially new solutions.

In a very recent study [16], data analytics and machine learning techniques are applied to improve building HVAC system’s energy efficiency with respect to the thermal comfort. Based on their exploration of the real-world data, it is found that the user-defined SetPoint Temperature (SPT) is always lower than the ideal SPT, which implies inefficient operation behaviour to consume energy. Therefore, a Majority Voting Classifier (MVC) that integrates three machine learning models: a RF, a SVM and an Extreme Gradient Boosting Machine (XGBM) is applied to autonomously adjust the HVAC system operation state considering both the energy efficiency and thermal comfort. Although RF, SVM and XGBM are all very successful machine learning models which were proved effective to deal with a variety of challenging difficulties, the highlight worthy further discussion is the MVC presented by Ruta et al. in [17].

Different from an individual classifier which output the predicting result based on a single classifier’s decision, MVC selects a set of classifiers from the large pool of different machine learning models and then ensemble them as a whole to make predictions. Many studies [17][18][19] believe that the ensembled MVC can outperform the single classifier with not only higher accuracy but also better robustness, since the team strength can adapt to more diversifying patterns and avoid overfittings. Because every base estimators in the ensemble model are trained independently to observe different (despite overlaps exist) aspects of the given dataset, the variance of predictions is expected to be reduced but keeping the bias level at the same [20]. An intuitive example from human’s perspective is that the critical decision made by a committee is typically more reliable than the one made by only a single expert, because the members from various backgrounds tend to consider a certain problem in a more comprehensive way. Fig. 4 compares the difference between a MVC and an individual classifier when they need to determine what the fruit with a bite off is. Despite a wrong classification made by one of the base estimators (member) in MVC, the final voting result is still right rather than the individual classifier fails to do so in this case.

2.2 Pillar II: Generation

Another fundamental topic in electricity systems that AI may play a crucial role in is forecasting electricity generation. With the booming development of renewable energy harvest techniques, renewable energies such as solar, wind and tidal power take account for bigger shares, becoming an important component in the electricity generation industry. Although the participation of renewable energy, to large extent, aids to mitigate the global warming effect and energy shortage by further increasing the clean energy supply, challenges remain. For example, the variability and non-schedulable nature flaws of wind and solar power plants can impose negative implications in technical and commercial operations and make the generation planning become challenging [21]. To solve these problems, a series of machine learning-based approaches are proposed and validated to help decision makers more easily manage the electricity systems.

Considering the wind power plants, the inherent variability and uncontrollable characteristics of wind power lead to difficulties in forecasting the short-, medium- and long-term generation capability. However, not only does the planning stage require accurate long-term predictions, but also the generation commitment and market operation need the medium- and short-term forecasts (for days, hours or even minutes) [21]. In the investigation [21], Michael et al. applied the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) that combines the fuzzy logics* with the Neural Network (NN) to forecast the short-term wind power. From the functional perspective, it inherits the interpretability characteristics of the fuzzy inference system and the learning ability of the adaptive network, so it is able to change the system parameters according to the prior knowledge. Their case study based on the real-world dataset from wind powerplants in Tasmania shows a 5% accuracy increasing compared to the benchmark persistence model, while more significant predicting improvement is observed when the wind power has suddenly increasing and decreasing changes.

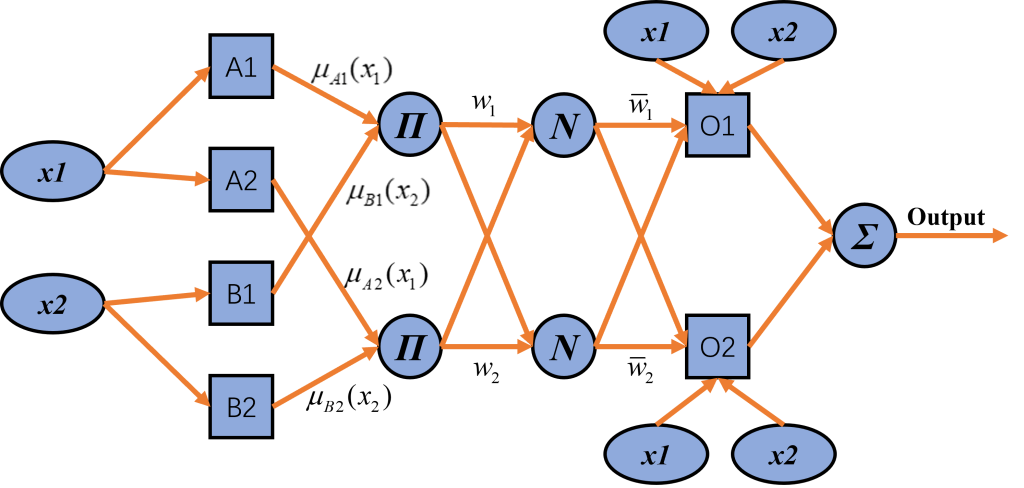

A typical 5-layer ANFIS structure is shown in Fig. 5, where the square node is the node with tuneable parameters and the round node is the node with fixed parameters. Each layer in the ANFIS takes their responsibilities, i.e., fuzzifying, computing the rule applicability, normalising, rule computation and outputting. We briefly introduce each layer from the left to the right as following:

The input features and

are fuzzified at the first layer of fuzzification by applying the so-called membership functions that maps the feature value into a fuzzy logic value

ranging from 0 to 1. Then, after the firing strength

is computed at the second layer of rule applicability computation by multiplying the fuzzy logics from the last layer, the firing strength value is normalised at the third layer of normalisation to represent the applicability of a certain rule during the inferring process (

). At the fourth layer of rule computation, the rule outputs are obtained before finally summed at the fifth layer of output to generate the predicting result. To optimise the tuneable parameters in the ANFIS, similar aforementioned forward and backward propagation techniques can be applied like a common-used ANN. In fact, this machine learning technique is also believed to suits generation prediction problem for other renewable energy powerplants, and thus worthy further explorations [21].

Fuzzy Logic

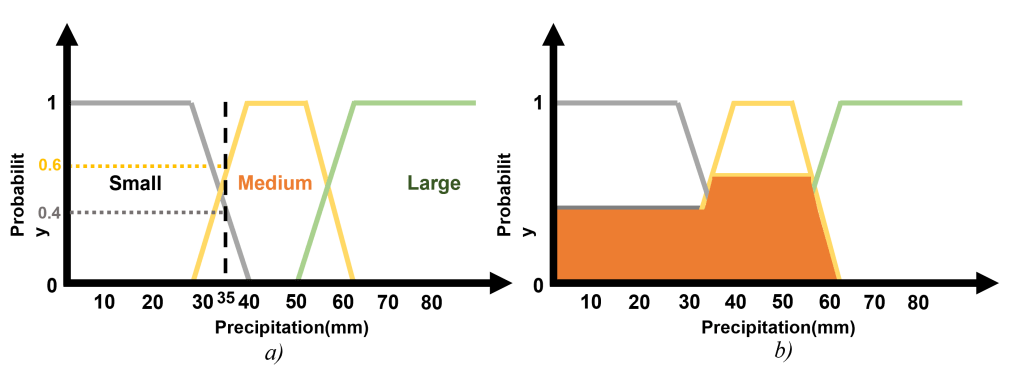

Different from the classic Boolean Logic that only permits two opposite logic values: true and false, the fuzzy logic tends to approximate how human beings make a judgement or decision, that is, there is not an absolute and clear boundary between true and false but considering the probability or so-called Degree of membership. For example, people always set a rule like “If there is heavy rain, I will take the umbrella.”, but a nature problem comes to “to what extent, the rain should be considered as heavy?”, or equivalently, “Should a 35mm precipitation be considered as a medium rain?”.

Fig. 6 a) shows a toy example of membership function for the discussed example. In this case, the fuzzified output should be:

A = {Small:0.4, Medium:0.6, Large:0}

Instead of absolutely clarifying it is a small or medium rain, the rainy state is represented as “60% chance of small rain and 40% chance of medium rain.”. Alternatively, a single representative value can be computed by using method like Centre of Gravity Defuzzification illustrated by b), which can be expressed by the equation below:

, where the gravity centre y* of the orange area shown in b) is regarded as the state of rain that may inform the inferring system in a more generic way.

2.3 Pillar III: Distribution

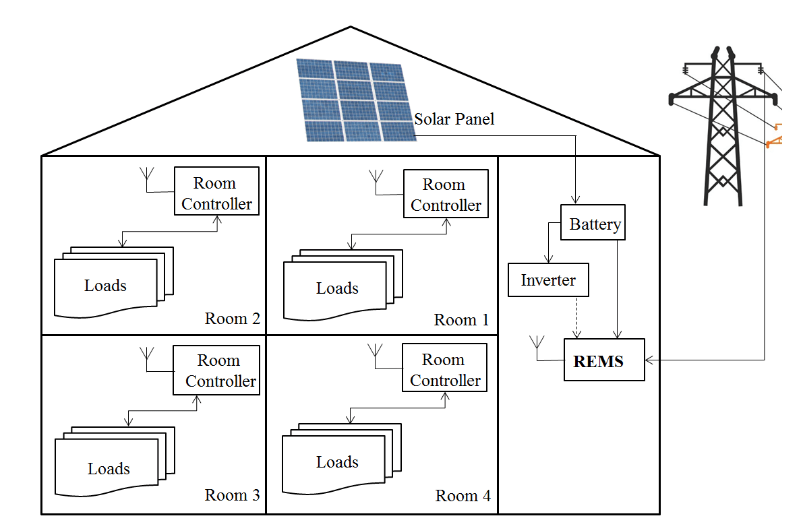

As for the electricity systems, it is not enough to pay our attention to optimising the electricity consumption and generation only. As discussed, the electricity distribution system is an important complementary component to the modern electricity systems, which is expected to shave the peak and fill the valley to avoid energy waste. Except for reviewing the electricity distribution mechanism from a macroscopic aspect for a better and more efficient demand-supply match, it is valuable to have a deeper insight from the smart grid closer to the edge, for example, the Residential Energy Management System (REMS) [22]. New findings in the distributed energy exploitation and large-volume storage battery make it possible to intelligently conduct the charge-discharge transactions to switch some of the loads to the local energy storage units energised by renewable energy sources at the domestic level. In spite of difficulties in controlling the smart switchover between the local and the external electricity source, machine learning techniques are believed to have a promising performance to deal with this problem.

In a recent study conducted by Krishna et al. [22] that aims to set up a smart REMS to reduce the energy consumption from the external transmission line, shown in Fig. 7. Controlled by a master controller and s set of slaved room controllers, the local storage charged by solar panels is used to power up the appliances with suggested decisions [22]. Meanwhile, because the system is also connected to the external public electricity system, the power supply is ensured while attempting to enable the consumers to live a low-carbon life. As the core of the REMS, a popular traditional machine learning model SVM is applied to guide the management policy of the master controller, which is experimentally proved superior to other approaches even ANN. Therefore, it is vital to figure out some principles of the SVM and to know how it works.

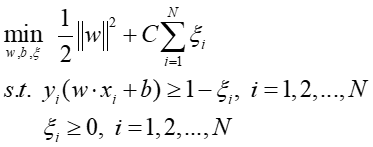

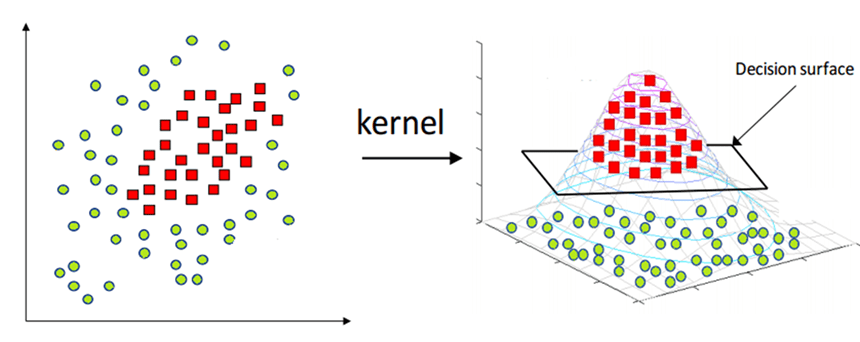

The basic idea of SVM is to maximise the margin between different classes and then determine a decision boundary that can well separate them. An intuitive understanding is that the SVM’s decision boundary should be as far away from the data points from different classes as possible. While the nature of hyperplane fails in dealing with the non-linear separation problem, kernel tricks can map the input data into a feature space with higher dimensionality and sparsity. Furthermore, penalties are typically applied for the misclassification allowing the soft margin of decision boundary . Briefly, the SVM with a given decision boundary is optimised by finding a set of parameters

and

that can broaden the margin

as wide as possible. Because the margin width, in fact, is limited by the data points at the most inside location, these data points are thus called support vectors, shown in Fig. 8. Bear with a bit more mathematics, the optimisation problem to find the best decision boundary with soft margin penalty can be written as follows:

, where is the penalty coefficient and

is the errors of misclassification. This optimisation problem can be easily solved by using the Lagrange function and multiplier.

Kernel Tricks

Fig. 9 illustrates an example of applying kernel tricks to map the input data from low-dimensional space to a high-dimensional space. Obviously, for the original inputs, it is impossible to use a straight line to classify the class of red from the class of green (not linear separatable). However, after applying the kernel function that assign a new dimension at direction and rising the samples from red class higher, using a decision plane (boundary) to separate them the two classes from each other becomes much easier. In this case, the classification in the high-dimensional space is linear separatable. In fact, it is the kernel tricks that make the SVM so successful in various challenging scenarios, because it can finely solve both the linear and non-linear problems by carefully selecting a proper form of kernel function.

3. Ethical Implications: Black-box Interpretability, Risks and Bias

In the previous sections, we have seen that the machine learning techniques are able to improve the current electricity systems significantly and even promote the profound transformation of the industry. However, technology is always a double-edged sword, and thus it needs careful evaluation, strict supervision and timely intervention. Otherwise, a series of negative ethical implications may exceed the advantages it brings to us. In fact, many concerns of widely applying machine learning techniques into every corner of our lives have been raised and debated for years, e.g., the model interpretability, potential risks and bias. Therefore, we discuss two interesting topics in this section, i.e., how the black-box nature of machine learning models and potential bias introduced by the purely data-driven approaches impact future electricity systems. The two inherent factors actually lead to potential risks that prevent machine learning play a more important role in electricity systems.

It will either be the best thing that’s ever happened to us, or it will be the worst thing.

——Stephen Hawking

3.1 The Black-box Nature of Nowadays Machine Learning Systems

Thanks to in-depth exploration and research, the forecasting performance of machine learning models has been improved significantly, but nothing comes without a price—the model interpretability and transparency also become weak at the same time, so-called black box. Unfortunately, the trade-off between the model performance and the interpretability is fundamental and fatal, which means pursuing the model’s predictive capability alone tends to bring a series of unforeseeable risks and ethical consequences. It is acceptable to scarify certain model transparency to gain a promising model performance for some less crucial applications like entertainment, translation and common decision making, but the demands of trusting the black-box model require a comprehensive understanding and reasonable interpretation when machine learning techniques go further to some regulatory industries and make far-reaching decisions [23]. Those machine-made decisions may affect our lives or even the history of human beings, and thus we may expect to review and explain the models’ internal logic and reasons to make decisions before finally conducting them in practice.

In fact, there are many rising concerns that attract discussions from all parts of society. For example, many applied machine learning systems are proved to be fragile to adversarial attacks. Deng et al. in their investigation [24] found that slight and invisible changes of a few pixels for the road signs’ photo are likely to mislead the autonomous driving system outputting a wrong recognition result. This flaw is dangerous and fatal that can lead to serious safety consequences. Another risky scenario of applying unexplainable machine learning models in practice should be carefully considered by most business owners. Enterprises do not expect or even cannot bear the economic and security risks of taking influential decisions made by an unknown black box because of a lack of confidence. In most cases, you will not expect the board and stakeholders to have machine learning-related professional backgrounds, so it would be difficult to convince them to believe a machine-made decision if there is not a reasonable explanation of how a certain decision or prediction is generated. In the healthcare industry, the black-box nature also prevents the further exploitation of machine learning techniques [25]. Although they have been used in healthcare fields to recommend treatment measures, assist doctors in analysing complex bioinformatics and diagnosis, the persuasiveness is not so enhanced because medical actions sometimes are highly risky.

Therefore, attempts are continuously made to open the black boxes by enhancing the machine learning model interpretability, while keeping the predictive capability at the same time. In fact, previous and ongoing investigations mainly start from two perspectives to explain a black-box model, i.e., global interpretability and local interpretability. Briefly, global interpretation techniques aim to figure out the overall mechanism (or in average meanings) of the black-box model to improve model transparency. On the contrary, local interpretation techniques begin from a single or a small group of samples, trying to find the causal relationships between the targets and input features locally.

Bias in, bias out.

——Sandra G. Mayson

3.2 Machine Learning Amplifies Bias

Despite of criticism, it is still unavoidable for human beings to make biased decisions because of the decision maker’s personal experience (anchoring bias) as well as the inconsistent but more familiar prior assumptions (availability bias) [26]. Until today, our society still suffers from a range of discriminations and bias in recruitment, college admission, criminal conviction, to name but a few, though we are trying to mitigate their affections. As a data-driven technology, the AI’s thinking logic depends on the data that it sees and learns, and thus bias is very likely to be introduced (even amplified) in the machine learning models as well [26]. In fact, even though AI engineers and data scientists have no initial intention to introduce bias into the trained model, it still exists because the model re-learnt it from the originally imbalanced and biased dataset. Another important reason of forming bias in machine learning systems is from the inherent nature of some machine learning models. For instance, the ANN which imitates the working mechanism of human brains is likely to mimic the biased nature of us and thus potentials to make biased predictions.

In 2018, a disclosure reported that the automatic recruiting system of Amazon is not gender-neutral but preferring the males rather than female candidates. Accordingly, the bias in produced because Amazon’s machine learning-based recruiting system is trained with the submitted resumes over the past decades, while most of job applications were from males. Although this bias is clarified to be fixed by Amazon, experts still have concerns that if the recruiting system tends to discriminate applicants from other aspects in a more implicit way, e.g., class, race, nationality, etc. Furthermore, the potential bias of machine learning models may happen in the investment market as well. Because of the persistently pursing of excess investing income and pressure from the stakeholders, investment managers tend to prefer the model with only promising performance but ignore evaluate the model bias [27]. In financial services, discriminations and biased advice tend to be so nuanced that difficult to be detected. However, if this kind of bias and discriminations become common, the financial market might be unstable and fragile as a non-diversified and unbalanced decision pattern is applied.

To regulate these potential harms, not only AI model developers but also the government is responsible. In fact, Turilli et al. argued in 2007 that the consistency of the ethical principle should be ensured between the algorithms and human [28]. More recently, Neubert et al. further proposed that virtue should be considered as a framework to design an AI [29]. In other words, the negatives of biased training data need to be minimised to guarantee the ethical reasonability during the whole life cycle of an applied machine learning system. Fortunately, some governmental actions have been witnessed in recent years. The U.S. Congress have passed the Future of Artificial Intelligence Act in 2020 to regulate the possible risks and address the social concerns [27].

4. Conclusion

In this blog, we investigate a wide range of contents for the electricity industry ranging from the industry analysis and how the emerging machine learning techniques change it to the discussion of corresponding ethical issues. Firstly, after the history and current states of the electricity industry are Briefly reviewed, chapter 1 points out the main challenges in nowadays electricity systems from the perspectives of three fundamental pillars, i.e., electricity consumption, generation and distribution. Secondly, considering the significant potentials of machine learning techniques, some of the successful cases which applied them in electricity systems to improve efficiency and reduce energy waste are studied in chapter 2. Along with the case study, some of the applied machine learning models are also briefly introduced for the reader’s better understanding. Thirdly, in chapter 3, we go deeper to discuss some ethical concerns and challenges, that is, how the black-box nature of machine learning techniques and the bias introduced by them prevent their further advancement. According to investigations, not only researchers and engineers have been aware of these issues and set out to solve them, but also the government are intervening and regulating through both the legal and administrative approaches.

In conclusion, although there are still many challenges for the electricity industry to safely embrace AI technology, it is believed to be an inevitable trend that AI can make significant contributions to the industry through continuous exploration and discussion from all walks of life.

Reference List

[1] Smil, Vaclav. “World history and energy.” Encyclopedia of energy 6 (2004): 549-561.

[2] IEA World Energy Balances 2020 https://www.iea.org/subscribe-to-data-services/world-energy-balances-and-statistics, accessed on March 22, 2021.

[3] IEA (2021), Global Energy Review 2021, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2021

[4] Llorca, Manuel, Luis Orea, and Michael G. Pollitt. “Efficiency and environmental factors in the US electricity transmission industry.” Energy Economics 55 (2016): 234-246.

[5] Hannan, Mahammad A., et al. “A review of internet of energy based building energy management systems: Issues and recommendations.” Ieee Access 6 (2018): 38997-39014.

[6] Lee, Chijoo, and Hyungjun Yang. “A context-awareness system that uses a thermographic camera to monitor energy waste in buildings.” Energy and Buildings 135 (2017): 148-155.

[7] Doss-Gollin, James, et al. “How unprecedented was the February 2021 Texas cold snap?.” Environmental Research Letters (2021).

[8] Chua, Kian Jon, et al. “Achieving better energy-efficient air conditioning–a review of technologies and strategies.” Applied Energy 104 (2013): 87-104.

[9] Şerban, Andreea Claudia, and Miltiadis D. Lytras. “Artificial intelligence for smart renewable energy sector in Europe—Smart energy infrastructures for next generation smart cities.” IEEE Access 8 (2020): 77364-77377.

[10] Mosavi, Amir, Sina Faizollahzadeh Ardabili, and Shahabodin Shamshirband. “Demand prediction with machine learning models: State of the art and a systematic review of advances.” (2019).

[11] Suganthi, L., and Anand A. Samuel. “Energy models for demand forecasting—A review.” Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 16.2 (2012): 1223-1240.

[12] Torabi, Mehrnoosh, et al. “A Hybrid clustering and classification technique for forecasting short‐term energy consumption.” Environmental progress & sustainable energy 38.1 (2019): 66-76.

[13] Paterakis, Nikolaos G., et al. “Deep learning versus traditional machine learning methods for aggregated energy demand prediction.” 2017 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe). IEEE, 2017.

[14] Rumelhart, David E., Geoffrey E. Hinton, and Ronald J. Williams. “Learning representations by back-propagating errors.” nature 323.6088 (1986): 533-536.

[15] IEA (2020), Energy Efficiency 2020, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2020

[16] Grammenos, R., K. Karagiannis, and M. Escalante Ruiz. “Analysis and Optimisation of Building Efficiencies through Data Analytics and Machine Learning.” ASHRAE, 2021.

[17] Ruta, Dymitr, and Bogdan Gabrys. “Classifier selection for majority voting.” Information fusion 6.1 (2005): 63-81.

[18] Roli, Fabio, and Giorgio Giacinto. “Design of multiple classifier systems.” Hybrid methods in pattern recognition. 2002. 199-226.

[19] Sharkey, Amanda JC, and Noel E. Sharkey. “Combining diverse neural nets.” The Knowledge Engineering Review 12.3 (1997): 231-247.

[20] Breiman, Leo. “Random forests.” Machine learning 45.1 (2001): 5-32.

[21] Negnevitsky, Michael, Paras Mandal, and Anurag K. Srivastava. “Machine learning applications for load, price and wind power prediction in power systems.” 2009 15th International Conference on Intelligent System Applications to Power Systems. IEEE, 2009.

[22] Krishna Prakash, N., and D. Prasanna Vadana. “Machine learning based residential energy management system.” Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Research (ICCIC), Tamil Nadu, India. 2017.

[23] Mi, Jian-Xun, An-Di Li, and Li-Fang Zhou. “Review Study of Interpretation Methods for Future Interpretable Machine Learning.” IEEE Access 8 (2020): 191969-191985.

[24] Deng, Yao, et al. “An analysis of adversarial attacks and defenses on autonomous driving models.” 2020 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications (PerCom). IEEE, 2020.

[25] Miotto, Riccardo, et al. “Deep learning for healthcare: review, opportunities and challenges.” Briefings in bioinformatics 19.6 (2018): 1236-1246.

[26] Baer, Tobias, and Vishnu Kamalnath. “Controlling machine-learning algorithms and their biases.” McKinsey Insights (2017).

[27] Lee, In, and Yong Jae Shin. “Machine learning for enterprises: Applications, algorithm selection, and challenges.” Business Horizons 63.2 (2020): 157-170.

[28] Turilli, Matteo. “Ethical protocols design.” Ethics and Information Technology 9.1 (2007): 49-62.

[29] Neubert, Mitchell J., and George D. Montañez. “Virtue as a framework for the design and use of artificial intelligence.” Business Horizons 63.2 (2020): 195-204.